In Uganda, fake news isn’t just the difference between facts and fiction. It can be the difference between life and death.

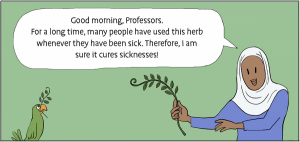

Nsangi is part of a project to change that. The tool: comic stories designed to teach Ugandan schoolchildren how to identify bogus health claims.

The target age group: 10- to 12-year-olds. They’re the current demographic sweet spot for reaching Ugandan children. Nearly half the population is below the age of 15. And at 10 and 11, the Ugandan kids are old enough to learn critical appraisal skills.

But there’s another pretty depressing reason: “We have very high dropout rates,” says Nsangi. “A lot of our children don’t continue on to secondary school.” So, public health educators have to reach them while they can.

Nsangi says using the comic art form was also motivated by practical matters. “They do not overwhelm children with too much text. Remember, English is not our first language. Most of these children are learning English for the very first time.” Comics get the important messages across without using complex English words.

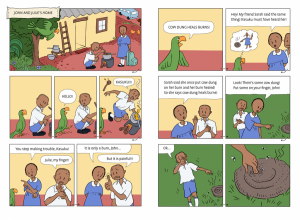

A typical lesson involves the popular belief in Uganda that cow dung heals burns.

After explaining how someone might believe cow dung is a cure for burns, the “Health Choices Book” gets serious.

“The comics bring the story to life,” Nsangi says. “Children are able to envision whatever story it is that we’re trying to tell them.” And learning critical thinking skills in the process.

Nsangi and her colleagues applied an end-user involvement approach to developing their teaching materials. And that meant introducing comics, which are not very common in Uganda.

“Some children were seeing comics for the very first time. So, we needed to do something that would be socially acceptable,” she says — yet, get the point across.

They started out with a small group of children whom they met with weekly to come up with a comic story the kids could relate to but also interpret and understand.

“We got to a point where it was the message the comics was communicating, not just the comic itself,” Nsangi says.

Eventually, the curricula included a cartoon-filled textbook, lesson plans and an exercise book, all on critical-thinking skills aimed at schoolchildren. Then, they introduced the materials in a number of Ugandan primary schools.

“What we’re trying to do is to try and get people not only to distinguish fact from fiction but equip them with critical skills that they will be able to use when making health decisions,” Nsangi says.

The efforts are getting the attention of the scientific community. In 2016, Nsangi and her colleagues tested the materials in a big trial involving 10,000 schoolchildren in 120 primary schools in the central region of Uganda. The results, which were encouraging, were recently published in The Lancet. They showed that kids who were taught basic concepts about how to think critically about health claims massively outperformed children in a control group.

Source: PRI